And I used to wonder where on Earth I was going to get Two Guineas for two tickets you see, to take this girl. Anyhow, a few days before the dance a letter used to arrive with two tickets in. No message. Nothing to say where they’d come from. But I think her father must have sent them to me. He knew I couldn’t afford to pay Two Guineas to go to a dance. It wasn’t long after going to these dances that I got very friendly with the family, the whole family. I used to see them practically every night; we used to go up there. Her father used to say “Have you got a few minutes to spare Basil?” so I said “Yes”. So he said “Come into the study” so I wondered what on Earth he wanted. Anyhow, he used to get all his share certificates out and he wanted me as a witness to his signature and we was about half an hour doing this and then he said “I think you’ve earned a glass of port now, for that, or sherry” and he used to give me a cigar as well and we were really very friendly indeed. I went out with her for five years.

This Mr Holborough, the girl’s father, he was in the wool trade in Bradford. They were pretty well off and I got on very well with him but after five years the mother, she seemed to be less friendly and she wanted this girl to break it off with me because of course I couldn’t get married on Thirty Bob a week. Not to keep her in the style she’d been used to being kept in. So we had to break it off. This girl, she didn’t really want to break it off with me. In fact, she knew a very rich friend who owned a lot of property on the front at Blackpool and she wanted to borrow Two Hundred Pounds from him and wanted us to elope. But this I wouldn’t agree to at all. I said “When I was in the position to marry her” I said “I would”.

We used to meet secretly quite often and go out together for an odd hour or two but we had to be very careful about it and not let her father and mother see us. Anyhow they found a new boyfriend for her and I don’t think she was very keen on him because she still used to see me occasionally. They used to go to these dances at the Royal Hall. Well the Royal Hall, it was a very large place. It had a huge dance floor and a raised circle at the back of the dance floor and then an upper circle. And two corridors with boxes down the side of the dance hall and a stage at the bottom where the band used to play. Well when I knew she was going to this dance with this boy and her father and mother, I used to go but I never used to dance. I used to go and have a drink and I used to keep my eye on her from the upper circle. And I’d catch her eye and beggle for her to come up to the upper circle. Around all the windows there were some huge velvet curtains that reached right down to the floor and we used to be talking. When we saw her boyfriend coming up, she used to slip behind these curtains. He used to say to me, he said “Where’s Eve? Have you seen her?” I said “Yes”, I said “She’s somewhere about. I’ve seen her but I can’t see her now” but I said “Didn’t you bring her to the dance?” So he said “Yes” so I said “Well surely you should look after her then” I said “When I used to bring her I used to look after her. She was never out of my sight” And he little knew that she was within a couple of feet of him behind these curtains. So I said to him, I said “You’d better go and find her” And so we used to have a good laugh about this.

The firm I worked for, the outfitter’s shop was WG Allen and Son. Well WG Allen, he was the boss. We used to call him ‘The Governor’. He’d retired semi-retired, and he used to come down about eleven o’clock in the morning and serve a few of his old customers and he never knew where anything was and he had me running round “Boy, get this! Boy, get that!” And I used to have to get all the stuff for him. One day, I found him lying on the cellar floor. He’d put some brown paper down and he was in his shirt sleeves and he had one of the man holes from the toilet open. And he was cleaning this toilet out with his hands. So I said to him “What ever are you doing there sir?” so he said “I’m cleaning this toilet out” so I said “Well, I would have done that for you if you’d only asked me” so he said “I’d never ask anybody to do anything that I wouldn’t do myself” I thought that was very nice indeed of him but I made him stop and I finished the job off for him. He was an Alderman in Harrogate and I think he was Honorary Chief of the Fire Brigade. I remember he had a little car which he used to drive. I was generally in the shop looking out for customers and as soon as I saw anybody come in I’d to open the door for them and take them to a seat. Well, suddenly I saw the Governor, WG Allen, tearing past in his car shouting at the top of his voice “Boy! Boy! Come here! Come here! I can’t stop it” And he was going round and round the war memorial in a circle. He couldn’t stop this car. So I had to run after him and last of all I jumped on the foot board but I didn’t know how to stop it either. Anyhow, last of all I found the ignition switch and I switched that off. So he said “Thank goodness you’ve come” he said “I’d have never been able to stop it” Luckily there wasn’t so much traffic about then as there is today.

Now, his granddaughter, she was just the opposite. She couldn’t start the car! So she used to borrow me and go shopping in the car and I’d to sit in the car while she left the engine running as of course, as you know, you weren’t allowed to leave the engine running with nobody in the car. So I used to go out with her shopping and she used to terrify me the way she was driving round the town but we generally got back safely.

It was while I was at Allen’s in about Nineteen Twenty Three, I should think it would be, I’m not quite sure of the date, there was a General Strike on in England. All the trains and buses, everything closed down. So the boss asked me if I would like to volunteer to help during the strike so he suggested I joined the Special Constables. This I did. We used to do one hour on watch in the station, half of us, and the other half were on point duty for an hour. Just two hours a day. That was what I said I could do. Well, the first point they put me on, there were five roads, it was near the Valley Gardens, five roads converged there. They issued us with a truncheon and a big policeman’s cape. Well, when I got this cape on I found I couldn’t get my arms out to signal. So there was chaos of course. So I had to take the cape off and put it down on the footpath. We used to do our hour there and then we were relieved and we used to go back in the police station for an hour.

I don’t know how long this strike lasted but it was a fortnight or three weeks I think. I remember, I was put on point duty at the Royal Hotel one day and they’d never had a policeman on duty there at all. It was just a tee junction by The Stray. Not a very busy one at that. But further down at the Prince of Wales corner was a very busy crossroads and we used to be taken down by a Major, he was in charge of the Specials at that time and just as we got to Prince of Wales, I was in the car going on duty, he was going to drop me off at the Prince of Wales Hotel and he suddenly said to me, he says “Why didn’t you stop that car?” So I said “What car?” So he said “That was a wanted car that’s just gone past. So I said “Well, why didn’t you stop him?” I said “I was in the car. How do you expect me to stop him” I said “I was in the car with you” So he said, “You weren’t” he says “You’ve just been relived from this point” So I said “I certainly haven’t” I said “I’ve just come on. You’ve just brought me here now in the car” Anyhow, it should have been the other chap that’d have stopped him. Anyhow, I’d never heard anything about this car being wanted. So I think that got his back up a bit, seeing that he’d made a mistake like that. Anyhow, we used to go out every day. Very often at night, we were called out at night to patrol a goods yard. They were doing a lot of sabotage, the pickets and what not at Starbeck. We used to have to patrol round the goods yard to see all was well. Towards the end of the strike I was put on point duty at this Royal Hotel corner. I could see the Price of Wales corner about a hundred and fifty yards away. Anyhow, I’d been there about three and a half hours. I’d seen the chap at the Prince of Wales being relieved twice and they just went past me and left me there. So last of all I thought “Oh, blow this and I’ll go back into the police station”. So off I went to the police station and said “Why hadn’t I been relieved?” so this Major said “What do you mean, ‘why haven’t you been relieved?’” he said “Where from?” So I said “The Royal Hotel corner” so he says “What? Do you mean to say you’ve left your post without being relieved?” I said “Yes, I certainly have. I’ve been on three and a half hours and I’m only supposed to do two hours. That’s all I joined up for” And of course he was talking in front of all these chaps who were in the police station on watch and he said “Do you know” he said “When I was in the Army, I sent men out into the desert with one days rations and they used to stop there as much as three days and never asked why they hadn’t been relieved and they used to stay there?” And I said “Well, I’m sorry about that but” I said “there isn’t a war on and I’m not getting paid for it and” I said “I hadn’t any rations with me and” I said “I’ve got another job to do” so I said “I think I’ll resign right here and now. Good afternoon!” So off I went back to the shop and of course the boss asked me where I’d been all this time. I’d got all the post parcels to get ready and everything. He was in a bit of a rush.

I remember my friend. A chap called Bert Lister, he was driving the train and I don’t think he ever pulled it up at the platform. He either overshot it or stopped too soon. People had to get out on the line. I suppose it was rather difficult to stop trains if you weren’t used to them. Anyhow, I think it was the day after I resigned, the strike ended and so all was well. We didn’t have to go out anymore. I think if I hadn’t gone back to the police station I’d still have been on point duty there yet!

After the war, when my eldest brother Bill came out of the Army, jobs were very far and few between and he went to Manchester and got a job at the Westing House there. They wanted him to join the union and he refused. So he was always having rows there with the union people. So after a few months he left them and he got a job in Nigeria working for one of the big combines there. He was out there eighteen months and I don’t know much about what happened then but at the end of eighteen months he came back home. He liked it very much in Nigeria and my brother, Rudy, he tried to join the Army before he was eighteen but they wouldn’t have him. On his eighteenth birthday he joined the Army and he was sent out to Germany with the Army of Occupation out there. While he was there he went to call on my cousin, Lawrence Buhlmann who, as I said previously, had been working with my father in England years before then. When this German cousin of mine saw him walking up the garden he thought “Now what have I done?” He thought he was in trouble with the soldiers. Anyhow, my brother told him who he was and they had a jolly good time together.

When he came home he went back to the bank. Barclays Bank in Harrogate. He was working there. As I said, my brother Bill, he liked Africa very much and he persuaded my brother to leave the bank and go out with him back to Nigeria to do a bit of trading with the natives. This they did. But it didn’t turn out a huge success. I suppose they were they eighteen months or so. I don’t really know really what happened out there but suddenly my brother Bill was taken seriously ill with some tropical fever. All the doctors had given him up they said he couldn’t possibly live. So my brother Ernest went to see him in hospital and he said “You bloody well would go and die and leave me in a mess like this” he said “it’s just like you” he said “Just die and leave me in all this jam out here and let me get out of all the trouble we’re in!” Well with this, my brother bucked up quite a lot and he recovered so I think the telling off did him quite a lot of good. Anyhow they were dead broke. They didn’t do any good at all out there and Bill, he came home but Rudy, he got a job with a man working out there, they were getting mahogany out of the bush at a place called Satteley and my brother’s boss was called Bartlett. He lived in Liverpool. He used to drink very heavily and the doctors told him that if he went out there again… they sent him home… they said if he went out there again he’d die out there, he wouldn’t come back. So my brother suggested that I might take on the job of reliving him. Go out there and work for him. So my brother Bill took me over to Liverpool and we saw this chap, Bartlett and he said “Oh yes, I think it’d be a jolly good idea” he said “I’d be very pleased if you would go out there” So I said “When would you like me to go?” so he said “Well, I’d like you to sail soon after Christmas” So I told my boss at Allen’s, I said “I’d got a job in Nigeria and they wanted me to go just after Christmas so I’d like to give my notice in. Well they were very good about it. They gave me a gold watch, the boss did, and the staff, they brought me a Rolls Razor and they were very good to me indeed. And I still have that watch. It keeps perfect time even today.

Well I waited and waited for this chap to let me know when he wanted me to sail and then to my surprise I got a letter from my brother Rudy to say this chap Bartlett had gone back again to Nigeria. And in a few weeks he died. So of course that job packed up and it left me without a job and I didn’t feel like going back and asking for my job back at the outfitters. It was a pretty tame job and I wanted some excitement. Both my brothers had been out to Africa and I thought I’d like to go abroad somewhere. There were no jobs at all to be got at that time. There was a real slump on in England and I was on the dole. One day the chap at the Labour Exchange, he said “We’ve put you down for going to Canada” so I said “Oh, have you?” so he said “Yes” I said “Well what are the terms like there?” He said “Oh, it’s a very nice place, Canada” and he said “We give you a pair of trousers and pound to spend on the boat and we pay your fare out there” so I said “What about paying your fare back? Who pays that?” so he said “Oh, you’ll have so save up for that yourself if you want to come back” so I said “Well you’d better rub my name of, I don’t think I’m going” he said “Well there’s a film on at the Royal Hall showing all about Canada so we’d like you to go and see that” so I said “Oh, I’ll go and see that alright” So off I went. Well, it was beautiful film. Beautiful sunshine. Corn growing. It looked really smashing.

I was going to get ten shillings a week while I was in Canada so I thought it would take me a heck of a long time to save up my fare back at ten shillings a week. So I told them at the Labour Exchange, I said “Don’t they have any winter in Canada then? He said “Yes, of course they do” so I said “Well it didn’t show anything about that on the film” so I said “Anyhow, I’m not going” He said “Well, there’s nothing to keep you in England” so I said “I’ve got a widowed mother to keep or help to keep, at least” and so I said “Anyhow, I’m definitely not going” so that was that.

While any of us boys were away abroad, my mother, she wrote every week, no matter where we were. One night, I was going to the Royal Hall in fancy dress and I got dressed up as the devil. I got a pattern and I made this costume myself. I got a bowler hat and cut the brim of it and stuck two trumpets for horns in this hat and of course had my face painted bright red and a black moustache and a black beard and a huge red cape and red tights on. And my mother said “Oh, it’s mail day today. I must get this letter posted at the General before eight o’clock” so she said “You’ll have to take it” So I said “How on Earth can I take it” I said “I can’t go out like this” I said “They’d lock me up!” Anyhow, I’d got a motorbike and she insisted that this letter went so off I went on this motorbike. Well, I was feeling such a fool on this bike that I’m afraid I was going very fast and I shot across the road near the war memorial and a car saw me and I think he got such a shock that he swerved and I swerved and I went over the grass of the war memorial which was close to the Post Office and went to the Post Office, popped the letter in and came back another way because I thought the police would be after me! I don’t know what on Earth this chap in the motor car thought of me. I think it caused quite a sensation in the town.

Anyhow, I got back home and then I went back to the Royal Hall and I went in a taxi and the headlines in the Leader Mercury saying “The Devil dances to American Jazz”. I remember I’d gone with Thoma Ryder that day and was dancing with her quite a lot. I got first prize for it.

When my brother Ernest got a job with this chap called Bartlett, my other brother Bill, he came home. I think he got a job in Portsmouth. When this chap, Bartlett died, of course, my brother Ernest had to come home as well. He lost his job. Well, he got a job as a motor sales man in Harrogate and worked there for quite a while. A friend of his saw an advertisement in the paper asking for a manager for a job in Kenya for the East African Mercantile Company. So my brother applied for that job and he got it alright. So he went out there and he’s been in Africa ever since and he’s still out there now.

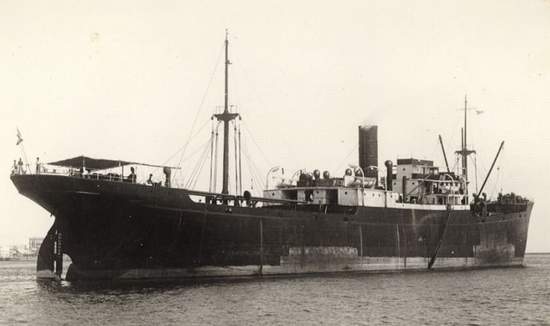

I must have been out of work quite a few months. Six or seven months, at least. My mother had a lady living with us in the boarding house whose brother was the secretary of a steam ship company in West Hartlepool. One Saturday afternoon he came to see her and she evidently told him about me being out of work and was there anything he could do. So he called me upstairs and said “Would I like to go to sea?” so I said “Yes, I certainly would” so he said “Right, when can you leave” so I said “As soon as you like” So this was Saturday, about midday. So he said, “Well, if you can leave tomorrow morning about Seven o’Clock and catch a train to Port Talbot in South Wales, you can join the Apsleyhall as a Mess Room Steward” So of course I had to go dashing about the town, buying various things to take with me and I’d to pack in a great hurry. I didn’t know how to get in touch with my girlfriend but I decided to phone her up. If she hadn’t answered, I was just going to put the phone down again. Luckily she did answer the phone. I told her, I said “Look”, I said “I’m going to sea tomorrow so I won’t be seeing you anymore. Could you see me tonight?” So she said well, she was going to a party but she said “I’ll make it” and so she did and we had a couple of hours together. We met near our house and sat on a seat and talked things over.

This man who’d given me the job at sea, he said if I went to sea for a couple of years and roughed it, he’s give me a job in the office so I thought this would be pretty good. I’d be able to get on and perhaps get somewhere. So I caught the first train on Sunday morning for Port Talbot in South Wales. When I got to the docks, it seemed just one mass of railway lines and goodness knows what so I didn’t know where on Earth to look for this ship so I asked a Docker, I said “Have you any idea where The Apsleyhall is?” so he said “Yes, it’s just over there” So I went along there and there was no gangway there. Just a ladder. So I had to struggle up this ladder with my luggage. Well, when I got on board I met a chap who turned out to be the Steward so he said “Who are you?” so I said “I’m the new Mess Room Steward” so he said “You’re not you know” he said “we’ve already got a Mess Room Steward” so I said “Anyhow, I’ve been sent here by the secretary of the company and he said he’d got a job for me here and I’d to report to the Captain” I said “Where is he?” So he said “Well, he’s ashore right now but he won’t be long. He’ll be back very soon” So I introduced myself to him so he said “Oh yes” he said “I’ve heard about you, I knew you were coming” so he said “Have you got a bed?” so I said “No” so he showed me my cabin and all there was, there were some four by two planks to lay on. No mattress or anything. So I thought “This is pretty good” But anyhow he called me up to the Bridge and he gave me a mattress and some blankets so I put those in the bunk and I was alright. It turned out I was sharing the room with the Cook. There were thirty three men on board altogether. I think were six Firemen, six Sailors, three Apprentices, a Mess Room Steward, a Carpenter and Boatswain, myself and the Cook, four Engineers, the Steward, Wireless Operator, a Donkeyman and the Captain.

While we were at Port Talbot we were loading general cargo, railway lines and all kinds of things to be taken to Madras. Well they just seemed to sling a chain round these railway lines and pull them up and these lines were hovering over your head and I didn’t feel very comfortable walking underneath cos I was certain one of them was going to slip and it’s no joke getting a crack on the head with a railway line. They evidently knew their job and nothing did fall.

The day of sailing. Well I was very excited about that. For the first few days I was alright but when we came to the Bay of Bisque there was a pretty heavy swell and I was very very sick and I kept going to my bunk and lying down. But the Steward said “Come on” We’re not having this. You have to get on with your work” So he used to pull me out of my bunk and I used to carry on working and when he disappeared I used to nip back to my bunk but it was no good, I had to carry on. After a few days after we’d crossed the Bay of Bisque I was alright and felt fine. Nice sunny weather and it was glorious. I think the first port of call was Algiers and there we were taking on coal for our own use to burn on the ship. The way it was loaded, there were Egyptians, they had a plank from another boat and they were carrying up this coal in little baskets on their heads. I thought they seemed to be dropping an awful lot of coal into the sea. They seemed to be dropping some out of the basket every time they came up. Then I noticed there was a boat moored closed to and there was a diver down below and this diver was filling this coal into baskets and hauling them into this boat. I suppose they must have tipped these men who were putting coal on our ship so much to drop a bit off now and then and I think they were making quite a packet out of this. It didn’t take us very long to take on the coal because we hadn’t burnt a great deal coming from England. So we were on our way again.

The next stop was Port Said. We stopped there a day or two. I don’t know why but I thought it would be nice to go for a swim. I couldn’t swim but a lot of the apprentices, they were very good swimmers and they were swimming about so the Steward said he would lend me a life jacket. He said it was a Navy issue. He must have been pulling my leg because I got this life jacket on. It just seemed to be a rubber ring covered with felt. They’d lowered the gangway at Port Said. It didn’t quite come to the water’s edge but I walked down it and dropped off in to the water. Well, I went down down down and I thought I was never going to come up again. I couldn’t reach the gangway and this thing wasn’t holding me up so I hollered out and last of all one of the chaps on board saw me and throw me a rope so I climbed up on to the gangway. Well, I played hell with the Steward and I said “If that’s a Navy issue, God help the Navy!”

The water there was beautifully warm so I thought I’d like to go in again but I thought I’d have a proper life belt this time so I nicked one out of the life belt locker and put a regulation life belt on. Well, I jumped off into the sea with this, down the gangway, and that kept me afloat fine. I was swimming away round the ship and having a jolly good time. I swam to the shore. We didn’t often tie up alongside the shore; we were usually tied to a buoy. Well I got to the shore and I stepped onto the sand and it was red hot! I burnt my feet so I had to jump back into the water pretty quickly! It was here that I saw my first sand storm. Well, they called it a ‘Willy Nilly’ on the ship. I’d never heard of a Willy Nilly before but it was a circle of sand going very very high into the air and moving along the desert, along the canal and taking this sand up and everything with it. I should think it was twenty feet wide. Luckily it missed the ship or else we’d have got blown over by it. Then we had to go through the Suez Canal. Well, the Suez Canal wasn’t wide enough for two boats to pass so we had to take on board three Egyptians and a small rowing boat and it had a search light on it. Whenever we heard that there was another ship coming, we had to lower this boat into the water and these Egyptians used to row out to the side of the canal and all along the canal there were huge bollards and they used to slip the rope over one of these bollards, one fore and one aft and then they’d use our winches and they’d winch us right to the side and tie up until this ship had passed. Then we’d to get the ropes off again and the boat would come back onto the ship and off we’d go again until we met another ship. If a tanker laden with oil came into the canal, it had preference over everything. Even over the biggest liners. And of course we had preference over nothing being such a small boat so we had to stop many times. It was here I saw my first locust. They were like huge grass hoppers and I remember they seemed to be all colours, red ones, yellow ones, green ones. They looked very nice. They used to fly on the deck. Admittedly, I only saw one or two. There weren’t many but they certainly were there.

Then of course we came to the Red Sea. I think that was the hottest place I’d ever been in in my life. It was bad enough going through as a passenger but having to work in that heat, it was terrific. I soon made friends with everybody on board. The captain, he was very good, very friendly towards me. He called me on the bridge one day when we were in the Suez Canal area and he said “You see that mountain over there Baysil?” He always used to call me ‘Baysil’, so I said “Yes sir” so he said “Well that is Mount Sinai” he said “I suppose you’ve heard about Mount Sinai?” so I said “Oh yes, I have. Thank you very much for pointing it out to me”.

At every port we stopped, we used to go on the Bridge and he used to dole out a little bit of money for us to spend so we could go ashore. Well my wages were only Four Pounds a month, he’d never give me very much. I used to get up about half past four in the morning and I’d to take the Mate a cup of tea and toast up to the bridge. I had prickly heat very badly, you got covered with a mass of red spots and it was very very itchy and I remember when I had to make this toast, I was dancing about in front of this fire and it was agony. Anyhow, he used to get his toast every morning, the Mate, the Chief Officer. One day, I suppose it was slightly burnt, and he must have been feeling off colour so he said “What do you call this?” so I said “It’s toast” so he said “It’s burnt bread!” He threw it over the side. So I said “Right, you’ll get no more burnt bread from me. You’ll get bread and butter in the morning”

When I went to sea, it was in Nineteen Twenty Eight, I’d be about twenty three. I weighed twelve and a half stone and was tough as leather. I used to get the stores on board and in those days I could carry a two hundred weight bag of sugar up the gangway with no difficulty at all. What bored me most on the ship was having to peel potatoes. We used to have them three times a day and it was no joke having to peel potatoes for thirty three men! The Steward always seemed to be buying the cheapest he could get and he used to buy very small ones. Of course it used to take me hours to peel these potatoes and I always used to peel the bucket after tea for the following morning breakfast. I used to leave these in the Galley. Well I found that during the night the Firemen were pinching these and making chips and when I woke up in the morning I found nearly all my potatoes gone so I had to peel another pile for them!

One the first trip I made, as I said before, I was sleeping with the cook. He was absolutely filthy. I’m sure if he took his apron off it would have stood up on the deck it was stiff with grease. Most of the crew, they never used to shave while they were at sea and they looked a real scruffy lot. Of course, the Steward, he used to shave because he had to serve the Captain. By the end of a fortnight they looked real scruffy. Well I used to shave every day. I was on board and I used to get a bit of time off in the afternoon and I used to put a clean singlet on and, all we used to wear was singlet, shorts and shoes. They used to call me ‘the passenger’ but if they had the work to do that I had to do, they wouldn’t have thought it would have been so much fun being a passenger. As we were going through the Red Sea, there was a place, a signal station, I think it was called Perim, and we had to show our colours and hang the ensign up and signal the name of the ship so that they could report back to the company where we were. Well the Captain gave the order for the apprentice to run up the ensign, well he put it on the stern of the ship and he hung it upside down and at half-mast. They told me afterwards that there was a mutiny on board and there was somebody dead. Anyhow when the Captain spotted this, the signal station must have asked what the trouble was by semaphore, and when the Captain heard about this, he played hell with this apprentice and told him to put it up properly!

After passing Aden we’d a long trip across the Indian Ocean to Madras and we called at Colombo but for some reason the Captain wouldn’t let anybody go ashore. We didn’t stay very long so we went on to Madras and discharged our cargo there. It took usually a week to discharge the cargo and in Madras we got to know some very nice people. A Mr and Mrs Chance, they were on a mission there, and they used to take us out on our days off and in the evening and we used to have a sing song or something like that and on a Sunday we used to take us off into the country. I used to like to get away as far inland as I could because I knew I wasn’t going to stop at sea and I thought I’d like to see as much of the country that we visited as possible.

While at Madras there was very heavy surf and we used to go bathing there. Well, we hadn’t any bathing costumes and I as I told you, I couldn’t swim so I just used to wade out as far as I dare and this huge surf used to carry me back on to the land again. I used to just wear some shorts, khaki shorts. We were told afterwards by this Mr Chance that it was very dangerous as there were a lot of sharks about there. The backwash of the surf used to draw us back into the sea again so we decided not to do any more bathing there.

At each port of call the Captain used to, we used to line up on the bridge outside his cabin and he used to give us some money to spend. Of course we’d to sign for it always and it came off our wages. He said “And how much do you want Baysil?” so I said “Oh, one or two Rupees sir” so he said “Oh, I can’t be bothered with one or two Rupees. How will fifteen do you?” so I said “Oh, that’ll do fine sir. Thanks very much” Well, a Rupee was only one and sixpence so it wasn’t very much. We used to go into town and we used to have a drink and have a look round the town and go to this Mission and various things and I don’t know what happened but one of us must have done something wrong, anyhow the police started chasing us so we were running away from them and we came to the port in Madras. There was a port there. The fellow at the gate, he saw the police after us so he says “Come on! In here” and he said “Into that room over there” so we used to dash across to this room and it was a dormitory and the chaps in there used to say “Come on, jump into bed” and we used to get into bed with all our clothes on and they used to cover us up and so the police never got us.

When we’d discharged our cargo at Madras we thought we would be coming home again but we were chartered by another firm, a shipping firm, to go up to Calcutta and bring coal down to Madras. It was about four day’s journey. Well, as we loaded up with coal in Calcutta, the ship used to become filthy and of course, as soon as we sailed, they used to get the hose pipes out and wash all the coal off. That took us about a couple of days and then we were in Madras unloading again and the ship was filthy again, the same thing happened again. As soon as we sailed we started hosing off and making the ship respectable again. I remember once when we were leaving Madras, the Ship’s Carpenter, his name was Merrick, and he said he used to be an international rugby player for Wales and it was his job to port the anchor, they call it weighing the anchor. Anyhow he’d been out on shore for a drink or two and he came traipsing along the deck and all he had on was a singlet. Anyhow, the Mate saw him and said “What the hell do you think you’re doing Chippy?” so he says “Oh, I’m going to weigh the anchor” and the Mate says “Well, you’re certainly not going to weigh the anchor looking like that!” so he gave him one punch and knocked him out. The sailors had to do the job for him.

We were on this coal run for four or five weeks I should think, going backwards and forwards to Madras and we got to know Madras pretty well. Well, it was so very hot there that we used to sleep underneath the lifeboats up on the lifeboat deck. Well, the carpenter and myself, we went to bed early one night around about Nine o’Clock and I fell off to sleep and I presumed the carpenter did as well. Well, when I woke up in the morning, there he was next to me but about the middle of the afternoon the police came on board and they said that one of our men had had a taxi running all round the town late at night and he beat the taxi man up and wouldn’t pay him his fare so the Captain, he called for all hands on deck and we all had to line up, every member of the crew had to line up on deck and the police had to pick this man out because the taxi driver was with him. They picked the carpenter out. So he says “Well I wasn’t ashore last night so “ he says “it couldn’t have been me” But they said “Oh yes, they were certain it was him” so last of all I had to speak up and I said “No, it wasn’t the carpenter” I said “I said he was asleep with me under the life boats at Nine o’Clock, we went to bed” and I said “when I woke up again, he was there next morning” I said “I’m certain he didn’t go ashore” so the Captain made me swear that this was true, which I did and so of course they wouldn’t let the police take him. It was about three months later he said to me, he said “Remember that night in Madras where they said I’d been ashore, Base?” So I said “Yes” so he said “Well, it was me” he said “I couldn’t sleep and there were you fast asleep so I thought I’d go ashore and have a run around the town” So it was him after all but of course I couldn’t say anything then about it.

I remember one evening the Chief Engineer wanted a bottle of whiskey so one of the Apprentices and myself and the Mess Room Steward, we went ashore to get him this bottle of whiskey. We went into a very low down pub and who should we see but a lot of our own Firemen in there. Well, they insisted on us having a drink. Well, I didn’t feel like one and they bought us a pint of Stout each. Well, I couldn’t bear the smell of it never mind the taste. I hated the stuff. So I tipped my mug behind the barrel. I daren’t refuse having one because these Firemen could be very nasty if you got on the wrong side of them. I thought well, now I’ve got rid of mine, I’m alright. The next minute I looked round and my pint pot was full again. The Apprentice, he’d tipped his pint into my glass! So I had to drink it and I was as sick as a dog afterwards.